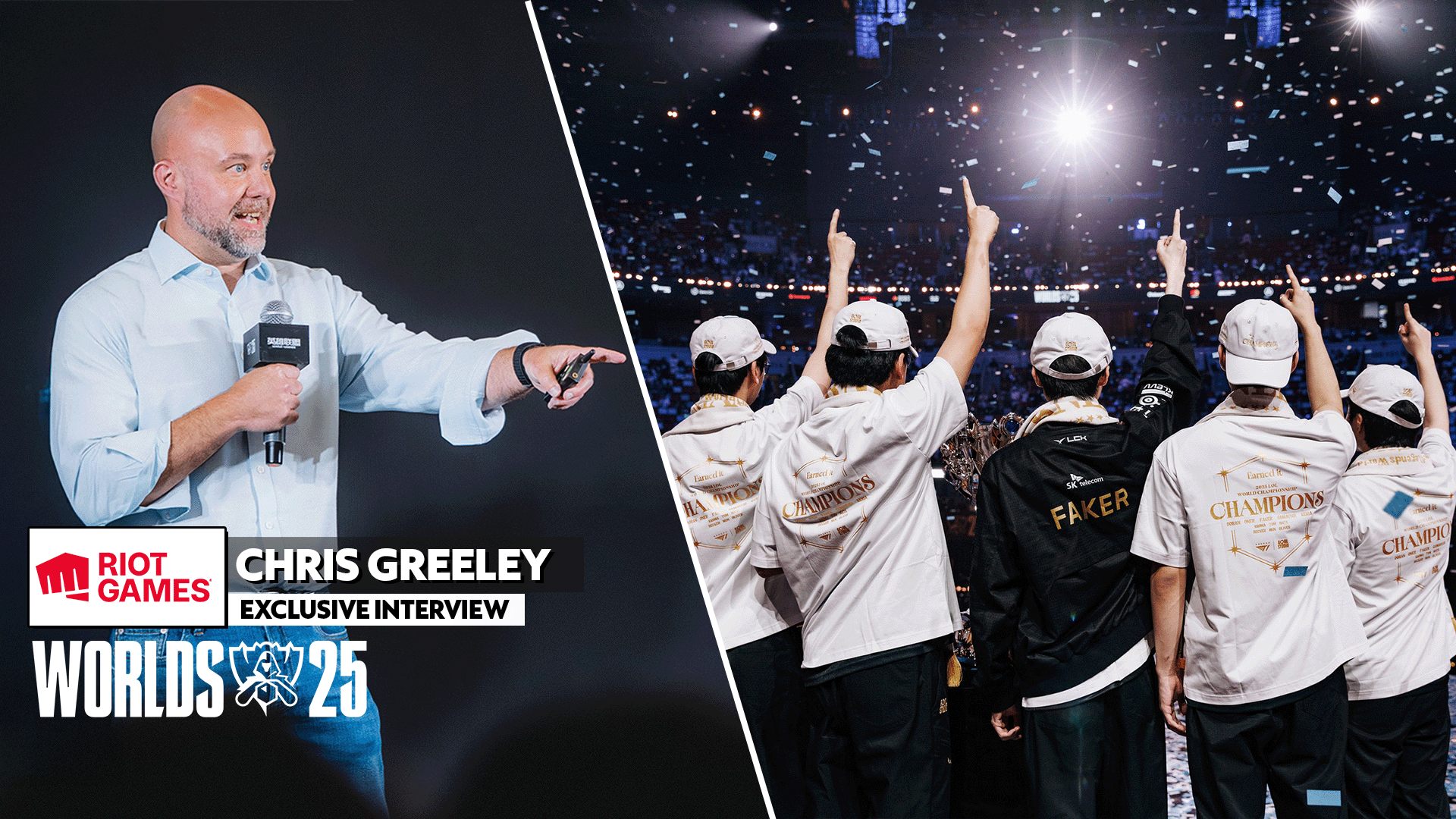

In just two weeks, many of the best League of Legends players in the world will converge in Europe for this year’s World Championship. But Alexey “Alex Ich” Ichetovkin, one of the West’s most gifted players, who once reached the semifinals at that annual event, won’t be there.

The 23-year-old Russian is the type of star you expect to see on that big stage. A clutch player tinged with a bloodthirst rare in the Western scene, only a handful of peers possess a League resume as extensive. But for the past two years or so, he’s only rarely appeared there, suffering through one of the poorest runs of luck you can imagine in a professional sport.

I’m talking to him late on a Summer night, and he mentions the weather. The temperature is always perfect in sunny Southern California, where he now lives, and that’s a welcome change from the icy winters he’s used to in Russia. “I like it a lot. It’s much better than cold!”

“Sometimes you try your best and it doesn’t work out and you just keep trying.”

The small talk is only natural. He’s a bit apprehensive about an interview, worried he’ll say something that ticks somebody off. Apparently that’s happened before (he didn’t explain further), but it’s almost hard to imagine. Ichetovkin is personable and friendly, and he exemplifies what it means to be an esports veteran and professional, even at his young age. That’s, in part, by necessity. He’s the only current League Championship Series player with a wife and child, and he talks lovingly of his family and the sacrifices he’s made for them. Still, Ichetovkin is a world-class competitor. He’s got the kind of competitive streak that typifies top athletes the world over, but it’s colored by a maturity that’s rare in esports players.

His team, Renegades, is a rag-tag bunch of veterans and up-and-comers with everything to prove who just qualified for the big leagues. But to Ichetovkin, that’s just the first step to “conquering the world!”

To be clear, that’s not just the World Championships. “I’m talking about conquering the world,” he says laughing. “It’s not Worlds, not League of Legends Worlds, right?”

He may have tongue firmly in cheek, but there’s a bit of truth to his quip. For Ichetovkin, there’s much more than building a competitive legacy on the line every time he’s summoned to the Rift.

Every game he plays isn’t just for himself and his teammates. It’s for the wife and child he supports. So when the promise of a stable job and salary seemed to stall with his career last year, it seemed like maybe it was time for him to move on from esports.

Then, in January, he relocated with his whole family to America, joining a no-name team that was trying to qualify for just the second tier of professional League of Legends int he U.S. It looked like a desperate gambit, like a fading star was making a last ditch effort to relive and revive his former glory.

It was one of the best decisions of Ichetovkin’s life.

The fall

In 2012, Ichetovkin was the face of the rising esport League of Legends. His fast-paced and lethal play made him one of the most feared players on the planet, a walking highlight reel who carried matches backed by his team, Moscow Five, and their creative style and perfect team fighting. They terrorized tournaments around Europe.

The team won what was at the time the biggest League tournament ever, the Intel Extreme Master (IEM) Season VI World Championship, early in March. That led to a fateful encounter. A Russian woman excited about her country’s victory in the big event messaged Ichetovkin on a social media network to congratulate him. The two started talking regularly. When he was hospitalized later that month, she took a big chance and travelled across Russia to visit him.

Later that year, the two married.

The team then won the European regional, securing a top seed at the Season 2 World Championships. Some analysts considered Moscow Five favorites, the strongest tournament team in Europe or America. But they would ultimately place fourth after losing to eventual champions Taipei Assassins in the semifinals.

Many players would be elated to earn a spot in the LCS. But in some ways for Ichetovkin, it was more a relief.

Ichetovkin would later say that’s when his team lost their “youthful zeal.” But in some ways that was inevitable. The foundation of their organization and the League landscape itself was about to change.

In June, Moscow Five owner and founder Dmitriy “ddd1ms” Smilianets was arrested in Amsterdam. At the time, the organization was unsure of his situation, but it was later revealed he was one of five people charged with running a hacking ring responsible for stealing over 160 million it and credit card numbers. By January, Moscow Five no longer had funding to support the League of Legends team, and that led the players to join Gambit Gaming. Around the same time, Riot Games, in a bid to step up its esports game and create the biggest professional league in the West, instituted the League Championship Series (LCS).

The regular league, with matches broadcast weekly from a central studio in Cologne, Germany, represented a new standard in Western esports. But for Gambit, it was the beginning of a decline.

While most teams relocated their operations to Cologne, for Gambit that wasn’t an option. It’s very difficult for Russian nationals like Ichetovkin and most of his teammates to secure work visas in Germany, meaning they had to fly in from Russia every week of the season.

Ichetovkin considered retiring. He had a child on the way, something he planned with his wife before Riot revealed the LCS. The huge travel commitment could put a big strain on his relationship, he believed, and esports is always a volatile career path. He could quit and get a job as a programmer, a career he pursued in Russia for two years before devoting himself to League full time. But Ichetovkin and his wife decided to give the LCS a shot.

In the Spring season, Gambit posted a 21-7 record before they lost in the finals to Fnatic. But their results steadily declined from there. In the Summer, they went only 15-13 before barely placing third in the playoffs, narrowly securing a spot at the World Championship, where they ranked in the top eight. The Spring season of 2014 went worse. After a 14-14 regular season the team placed fifth in the playoffs.

The rough travel schedule was getting to Ichetovkin, both on the Summoner’s Rift and at home. He’d fly to Germany midway through the week to compete at the LCS on Thursday and Friday, then head back home when matches were over. With two days of travel during every week, he had to spend almost every hour at home practicing.

“Those times were pretty exhausting for me and [my wife],” he said. They got “burned out” with all the travel. “I was just coming home, training all those times I come back, and just going back. We didn’t spend that much time together.”

That put a strain on his relationship, and naturally that began to affect his performance in-game.

“We were playing for playing instead of winning.”

“When you’re getting affected from something outside the game, it’s getting harder and harder to focus inside the game,” he says. “There are a lot of things that can distract you from game. Breaking from girlfriend, getting exhausted.”

The situation wasn’t ideal for the team, either. Valuable practice days were wasted with travel (Ichetovkin took a three-hour train ride to Moscow before a three-and-a-half-hour flight, meaning he spent eight hours travelling two days a week), and his fellow teammates were also fatigued. Edward Abgaryan and Evgeny “Darien” Mazaev had similar itineraries, though Ichetovkin thinks Abgaryan handled it a little better than the others.

Plus the team’s own success seemed to have gotten to their heads; they were stubborn and set in their ways, lacking the creativity that made them so dynamic when they burst onto the scene. Ichetovkin later said “we were playing for playing instead of winning.”

That led him to a hard decision. He left his team of three years, the team that took him to within two series from the World Championship, that won multiple IEM titles, in search of something better.

When he told the team that he was leaving, they didn’t believe him at first. Ichetovkin thinks his teammates probably thought he was experiencing typical post-season depression after a disappointing result, making a knee-jerk decision before changing his mind and returning.

But the calculated Ichetovkin doesn’t make reactionary decisions when it comes to his career. When he completed his departure, joining Swedish organization Ninjas in Pyjamas soon after, the team was surprised and angry.

“It was a really sad situation for both me and them,” Ichetovkin says. “I thought that it was a mutual agreement, and apparently it was not. I think if I told them earlier, or they understood me earlier, then it would be easier for them as an organization to get back into shape.”

Gambit struggled even more without Ichetovkin in the lineup, posting an 8-20 summer record that saw them playing in a relegation match, not the playoffs. Top laner Evgeny “Darien” Mazaev left the team midseason. Marksman Evgeny “Genja” Andryushin followed at season’s end. The Gambit Gaming of Ichetovkin’s heyday was no more.

The esports life

When the LCS went to Cologne, so did most of the team houses for pro teams. It only makes sense. You want a centralized location to practice, and when you’re playing multiple matches a week in that studio, proximity is important. It’s also likely a boon to the competitive level as a whole; the top teams and players get to meet and talk League, creating a hotbed for strategic innovation. For Gambit, the studio was in some ways a curse.

“I’m not sure if it killed team, but it was one of the parts that made it much harder,” Ichetovkin says. “There were a lot of different things that were making it harder and harder. It was just an unlucky streak, starting LCS then having the owner going to jail. A lot of other things were there. You never know how it would be if nothing of those would happen.”

In 2015 the European LCS moved to new digs in Berlin, and Gambit moved with it, buying a team house in the city and moving their team there. Abgaryan and Reshetnikov, the two of Ichetovkin’s former teammates still with Gambit, now live in Berlin during the season, their days of gruelling travel behind them.

If Gambit secured a team house setup and relocated their team earlier, or at least moved Ichetovkin (something they were at least considering before his departure) then perhaps this whole saga may have played out differently. Ichetovkin might be living in Germany and competing as a member of Gambit today. If Riot didn’t create the LCS, forcing its pro players to adopt a lifestyle different from the days heavy with tournament play, he might still be living in Russia, training hard for tournaments with more free time to spend with his family.

A rigorous travel schedule is often par for the course in professional sports. In 2008, the Seattle Mariners set a new MLB record for miles travelled with 55,000 over the course of their baseball season. But Ichetovkin likely topped that. A direct flight from Moscow to Cologne is 1,297 miles as the bird flies. Making a round trip each of nine weeks in an LCS season totals 23,346 miles. Over two splits, that’s 46,692 miles. Add in a little extra for events like playoffs and because Ichetovkin did not live in Moscow, and that MLB record crumbles.

In the fast-paced world of esports, the ‘what-have-you-done-for-me-lately’ mantra is law.

Plus, the length of the season itself is similar—at least so long as a League team qualifies for the playoffs and Worlds. The MLB season runs six months, with one month of playoffs and one month of spring training, giving players four months of vacation time. Two LCS splits plus playoffs run for six months, with another month for Worlds, means League players are working a similar length of time.

That means a League pro in Ichetovkin’s situation was travelling as much or more than a pro sports player, working as many or more hours, and had the same amount of vacation time, all without a seven figure or even six figure salary.

Even during the season they sometimes have more free time. One LCS team recently posted an ad seeking tryouts for its top lane position, noting that it’d require devoting 70 plus hours per week to League of Legends.

In sports like baseball, there’s a limit to how much a human body can train and work out. You can only spend so much time in the batting cage before your arm becomes fatigued. Pitchers have strict pitch counts limiting how much they train in between games. Muscles need rest and relaxation. Esports, on the other hand, is a constant grind, and there’s always someone practicing more than you. Every minute spent doing something else is a minute someone is using to surpass you. While it’s quite possible that the optimal esports training strategy may include more rest than is common today, right now—as far as we know—the best way to get good at League of Legends is to play it as much as possible, often at the expense of other activities like friends, family, and sleep.

That LCS schedule is also counter-productive towards building a more lucrative career in a world where entertainers get paid more than competitors, and competition is often just a gateway into the better paying and less stressful career of entertainer or spokesman.

Ichetovkin points to Jarosław “pasha” Jarząbkowski, a Polish Counter-Strike player with a huge following in Eastern Europe. Jarząbkowski became a father at the end of 2011, but Ichetovkin says he doesn’t have to deal with the same difficulties as a working dad in the LCS. In Counter-Strike, a game based on regular major tournaments, you only need to train intensely in the leadup to major events. Some teams play from team houses, but many others only bootcamp before big events. That kind of schedule, similar to the one featured in League before the LCS, gives players more freedom to spend time with family, something Ichetovkin envies.

That played into Ichetovkin’s decision to have a child back in 2012, when Moscow Five’s competitive schedule involved training for and attending tournaments like IEM, Major League Gaming, and the IGN Pro League. The LCS changed that paradigm, and eventually led him to America.

Rock bottom

After leaving Gambit in May 2014, Ichetovkin joined Ninjas in Pyjamas, an organization with a long and storied history in esports and excellent financial backing. The team featured a legendary Counter-Strike squad. But its history in League of Legends could best be described as cursed, with its latest attempt at reaching the LCS falling one game short.

With Ichetovkin in the lineup, the Ninjas looked like absolute locks to make the league in the Spring and challenge for a title in the Summer. They were playing like a top-tier LCS team but had to play in the Challenger Series to reach the next level. They frequently practiced against Europe’s best and beat them. They consistently dominated middling LCS teams. They had a few issues to overcome—jungler Tri Tin “k0u” Lam was too young to compete in the LCS at the time, for example—but that was something the star-studded lineup could handle.

For Ichetovkin, the team’s strength was appealing. In the Challenger Series, he could practice and compete from home, allowing him to spend more time with his family. Even better, the team offered a way into Europe. Ninjas in Pyjamas, based in Sweden, promised to help Ichetovkin and his family immigrate to Sweden. That’d get Ichetovkin into the European Union and potentially ease some of the travel burden that plagued him as a member of Gambit Gaming.

But something unexpected grounded the team. Just one month after Ichetovkin joined the lineup, Erlend “Nukeduck” Våtevik Holm and Alfonso “Mithy” Aguirre Rodriguez were suspended by Riot Games for “toxic” behavior through the 2014 season.

“I won’t give up,” Ichetovkin said at the time. “There are worse things happening in life. Sad morning.”

The team picked up replacement players and acquitted themselves well, placing second in both splits of the Summer Challenger Series. But they fell in the playoffs early to Unicorns of Love, preventing them from earning a promotion series and ending their LCS hopes.

“You can never expect that,” Ichetovkin told me regarding the bans, calling it an “unlucky streak.”

“Sometimes you try your best and it doesn’t work out and you just keep trying.”

“The only problem in esports is the investment is too risky.”

In fact, the two players in question are both now in the LCS, with Rodriguez headed to Worlds as a member of Origen. Marksman, Aleš “Freeze” Kněžínek, meanwhile, was recently relegated while playing for Copenhagen Wolves, but will likely sign an LCS deal before next season.

For Ichetovkin, the road was a bit longer. He had been living in Sweden training with the team, but when his temporary visa expired, with Ninjas in Pyjamas making no progress towards acquiring him a more permanent one, he left the team and returned to Russia.

In many ways, it sounded like his career may have been coming to an end. He made a statement on Facebook lamenting his situation. “I am too tired of fighting against me being Russian,” he wrote. “Right now I think there is almost no way for Russian player to get into somewhere because you can’t play anywhere except Russian leagues which are not that high skilled. It is like full isolation.”

The difficulty of travelling to the studio every week wasn’t the only problem for Russian nationals competing in the LCS. In 2014, Riot decided to host a week in London in the U.K., a place where the typical European Union travel rules do not apply. Gambit Gaming was only able to field one of their starting players due to their Russian players being denied visas in time. Ninjas in Pyjamas were forced to play without Ichetovkin.

Plus, Riot Games’ residency rules complicate matters. Riot’s rulebook states that all LCS players must be a “legal resident” in a country in their region. The company’s definition of Europe as a region explicitly excludes Russia, but since Gambit Gaming was already in the LCS at the time the rule was instituted, the players on the team were grandfathered in and made exempt. When Ichetovkin left Gambit, he forfeit that exemption. If he wants to return to the LCS, he can no longer commute from Russia.

That makes him a potentially risky acquisition for teams in the LCS—they would have to aid not only his immigration to a European country, but his family’s, before he can even compete.

Without an avenue to Europe like the one provided by Ninjas in Pyjamas, and with potential offers drying up, the situation looked bleak. Ichetovkin considered using his prior work experience as a programmer to get another nine-to-five job.

“I myself would have quit 100 percent in a situation like this, but my wife was strictly against it,” Ichetovkin said. She told him that they already decided to make a career in esports work, so he should keep going. They both knew it would be difficult, and that not everything would work out. And Ichetovkin was still confident in his ability as a player.

He knew he was skilled enough to be not only an LCS caliber player, but a world class one. He just hadn’t shown it recently, and in the fast-paced world of esports, where the “what-have-you-done-for-me-lately” mantra is law, that made it difficult to find an opportunity.

With economic problems looming in Russia, the time was simply right.

He solicited team offers, hoping to find one that could fix his situation, but he ended up playing with a local Russian organization, RoX.KiS, to maintain his skills. Playing solo queue alone isn’t enough, he says, since the five-on-five game is so different. Their scrims against European teams “didn’t look that bad,” he said. “We were actually doing super good. I was actually really confident.”

But his confidence didn’t lead to any enticing team offers, just “risky ones” from Challenger teams in Europe, who couldn’t offer any solutions to Ichetovkin’s situation in Russia. It wasn’t until December when Ichetovkin received an interesting solicitation from a man named Chris Vielman.

Vielman represented BrawL, a Latin American organization looking to expand into the U.S. The offer wasn’t exactly great. BrawL was unestablished in North America, and the team’s roster was hardly a lock to make the LCS, or even the Challenger Series itself. They weren’t offering a salary. The team wouldn’t even cover any of the travel costs associated with Ichetovkin moving to America. But they offered one key thing no one else did: a path to America.

Ichetovkin and his wife had been excited about moving to Sweden because of the opportunities it offered their family. The U.S. offered something similar—a solid economy, good schools, a high quality of life.

“She wanted to come to America,” Ichetovkin says. “She was like, ‘If we get a chance, let’s go!’”

While his wife had never travelled across the Atlantic, Ichetovkin had actually visited the U.S. multiple times while attending events. He said he usually got “annoyed” with long flights to most other places he’d visited. But when he flew to America, he said, “you felt like it was worth it.”

Vielman found it wasn’t a hard sell for Ichetovkin. He said the team had a shot at the Challenger Series and even the LCS, and introduced the team’s roster. But Ichetovkin didn’t really care. He didn’t really know any of the players in the American scene, anyway. With economic problems looming in Russia, the time was simply right.

Ichetovkin knew it was a risk, especially with a team of an unknown level. But he was confident that he could make his career work in the states. He was paying for his travel and for an apartment himself, and was confident he could at least break even through streaming while finding another opportunity if BrawL did not work out.

So he accepted.

Just a few short years ago, a Russian national getting a visa to play video games was probably a pipe dream. But in 2013, Danny “Shiphtur” Le, mid laner for Team Dignitas, became the first player to receive a P1-A visa for internationally recognized athletes after concerted lobbying from Riot Games. As long as a player can show they are competing at an “internationally recognized” level, they can receive a visa to compete in America for the duration of a competition or longer, up to five years without an extension. It makes the U.S. a hotspot for importing foreign talent, because as Ichetovkin puts it, “you just need lawyers that make sure the documents are 100 percent right.”

When Renegades imported Afghani AD carry Karim “Jébus” Tokhi, his arrival was delayed when he was denied a tourist visa. But his athletic visa came through with no problems.

Ichetovkin’s application went through smoothly as well. BrawL’s co-owner was good friends with Eric Ma, the manager of Team 8. Ma was a veteran of the visa process. He knew the right lawyers to push an application through after getting Braeden “Porpoisepops” Schwark and Ainslie “maplestreet” Wyllie, two Canadian nationals, their own athletic visas so they could compete in the LCS. Ma offered to facilitate Ichetovkin’s visa process in exchange for the Russian player’s services as a substitute for Team 8. Plus, placing Ichetovkin on an LCS roster, even as a substitute, made it easier to push the visa through.

“It just takes a long time or you have to pay a lot,” Ma said.

“Usually the trend is the harder you work, the higher you get. No matter of luck.”

In Europe, it’s easy to get what’s known as a Schengen visa, which can be used to freely visit a group of 26 countries in Europe, including Germany and Sweden, for up to 90 days. But it’s more difficult to receive a long term visa or a residency permit to not only visit, but live for the duration of an LCS competition, as they don’t recognize esports players the same way. Ichetovkin’s current visa lets him stay in the U.S. for two years, with an opening to apply for an extension to five once that period is up.

So in January, with an athletic visa secured and a dependent visa ready for his wife, Ichetovkin flew to America. But before he could play a single game, BrawL was eliminated from qualifying for the Challenger Series.

Coming to America

To an onlooker, it looked like a disaster. Ichetovkin’s potential return to the LCS was delayed at least another season unless he somehow found a spot on an LCS team. But that seemed increasingly unlikely considering it’d been months since he was seen in competitive form. He decided to stream for a bit while weighing his options. One was staying with BrawL and going all-in for the next season, something that might work assuming the team gelled and management was behind them. But then an interesting offer came from seemingly out of nowhere.

Chris Badawi, a charismatic former lawyer with designs on creating a team to reach the LCS, learned that Ichetovkin was in the country and possibly available. He contacted Ichetovkin and pitched a roster already featuring a veteran LCS jungler, Alberto “Crumbzz” Rengifo, and an organization focused on supporting its players. For Ichetovkin, it was intriguing, and the situation at BrawL seemed shaky at best.

“I decided it was too much risk,” he said of the BrawL situation. “It’s too much stakes for me, with the family. I think the organization understood themselves.”

Badawi contacted BrawL and “bought out” Ichetovkin, so to speak (he wasn’t formally contracted at the time). On March 9, Misfits announced its lineup: Ichetovkin, Rengifo, and support player Maria “Remilia” Creveling. The team sought tryouts for top lane and AD carry as they angled for a bid to qualify for the Challenger Series.

In May, they won the Alphadraft Challenger League title over Frank Fang Gaming and followed it in June by qualifying for the Challenger Series itself.

Things were finally looking up for Ichetovkin. His team was beginning the journey to the LCS, and looked like one of the favorites to win a spot. He was once again salaried, able to focus on honing his competitive skill. And he was playing and competing from home, with his family, his loving wife and growing child, at his side. But as Ichetovkin knows well, you can’t stay on top forever.

Backup plans

For a 23-year-old, Ichetovkin spends a lot of time thinking about his career and his future. That’s perhaps a necessity for someone in his position, with a family to support. But it’s certainly not common in esports.

Esports is a young man’s game. Most players are college age, with many barely out of high school. Some are even still attending. For them, esports is a hobby, a passion. A dream.

They don’t understand how spending some of the most valuable years of their lives in gaming instead of in school or building work experience might affect them five or 10 years down the line.

“It’s hard to just understand it’s a profession,” Ichetovkin says. “For most of them it’ still a hobby or something fun to do. The dedication is pretty low.”

That’s not much different than other sports, Ichetovkin says. Soccer players usually start playing because they love the game, and it only develops into a career when they realize they have the skill and dedication to make it possible.

In the game, he’s not afraid to take risks if the payout is worth it. And the same goes for his personal life.

In basketball, football, and soccer, there are better systems to mitigate some of the risks those young players take by devoting themselves to the game. University programs give players the chance to earn an education while learning if they’re good enough for a professional career (and if they aren’t, they can graduate school ready to work a job). Ichetovkin admires the collegiate system in America. Some of his Russian friends managed to attend universities in the states thanks to sports scholarships. And it provides a built-in safety net for players.

Plus, the reward for assuming that risk is higher in pro sports. The minimum salary in the NFL was $420,000 in 2014, for example. That’s enough money for a reasonable spender to support themselves for the rest of their life, after a short career. But in esports, a middling LCS player may not even make one tenth of that, which is no way to build a future.

Ichetovkin compares an esports career to starting your own business. Both take hours of dedication and hard work, with no guarantee of success or a return on an investment. Some people are content to work a job and make a steady salary to support themselves, but others are willing to sacrifice to reach a different goal.

“The only problem in esports is the investment is too risky,” Ichetovkin says.

For some, that may not be a big deal. Ichetovkin mentioned Steve “Calitrlolz” Kim, who recently retired after a year in the LCS on Team 8 to return to pharmacy school after taking a leave of absence to play competitively.

“[Cali] can just go back to his normal life and nothing happened from him being pro player,” Ichetovkin says. “Just a good experience and something to tell your children.”

For Ichetovkin, it’s a “really huge investment,” he says. “It’s very risky, but at the same time I have backup plans to go for if something doesn’t work out.”

How is he going to make money to support his family, and save money so his child can go to school in the future? How long can he continue playing and competing, when a game like League of Legends may not be around forever? Will his hands and wrists hold up for years of intense 10 hour days of practice? What happens if his skill wanes, players surpass him, or his team falls out of the LCS due to bad luck?

“You can get unlucky all the time in your life and you can get lucky all the time in your life,” Ichetovkin says. “Even if you work hard, sometimes you get unlucky. And even if you don’t work hard, sometimes you get lucky. Usually the trend is the harder you work, the higher you get. No matter of luck.”

That’s a statement that in many ways sums up Ichetovkin’s journey out of the LCS and back again. Through every trial, the one constant is that he keeps working hard. But it always helps to be ready for the worst.

For that, Ichetovkin says he’s always thinking about other opportunities or backup plans. He’s researching schools in America, thinking he might get a degree and have more security for his future. He’s happy in his team situation, but he builds relationships with other organizations to keep his options open if he needs them. He’s looked into the intricacies of streaming, studying the best times to broadcast, what content his audience likes, and what makes other popular streamers successful.

Streaming certainly looks like the ideal fallback career for a failing pro player. One analysis estimates that Team SoloMid superstar Søren “Bjergsen” Bjerg, probably the most watched streamer in League, makes over $20,000 a month from streaming, and that’s while maintaining his world-class level of mid lane play. But Ichetovkin believes steaming is much more difficult than it looks, and that Bjerg is an exception to the rule. He worries that focusing on streaming and providing an entertaining product for viewers is mutually exclusive from training hard as a professional player.

He’s finally firmly on the climb back up, ready to write new history of his own.

“I’d just need to put more effort into it, and it would probably prevent me from going competitive anymore,” he explained. “I wasn’t sure about that. It’d be 50/50. Because the more entertaining you get, it’s harder for you to keep competitive spirit and vice versa.”

When you watch an Ichetovkin stream it’s true you get high-level play, but he doesn’t have the type of personality that easily endears many of the biggest names to their audiences. He points to players like Joedat “Voyboy” Esfahani and William “Scarra” Le, who maintain big stream followings even after ending their playing careers thanks to their personality and ability to interact with their fans.

“I think my streams are kind of boring for some people to watch because I try to focus more on winning and playing competitive, so I don’t comment that much because I can’t focus on both at the same time,” he says.

Complicating matters is that most of his fanbase still hails from Europe, meaning his optimal stream times are out of whack with his current time zone. He’s found the best stream times are early in the morning or late at night, in the sweet spot where American streamers are offline and European streamers are just waking up.

“If you’re a streamer, you need to do it good,” Ichetovkin says. “If you want to play competitive you’re mostly thinking about the current meta. You’re watching Koreans. You’re trying your best. You are less entertaining and more try hard, and not everyone likes try hard over entertaining, so.”

“A lot of people say [streaming is] easy, but I think it’s as hard as maintaining, for example, a high level of play,” he said.

Some streamers have it easier due to a confluence of factors, like Bjerg. On a top team like Team SoloMid with a high level of individual play, Bjerg can maintain a massive following every time he turns on his stream, without too much effort. But someone like Mike “Wickd” Petersen has seen his audience dry up since his ousting from Alliance. That’s something that sometimes worries Ichetovkin. There’s no playbook on how to ensure people will want to continue watching you, especially if your professional career takes a turn for the worse.

That’s why Ichetovkin is always on the lookout for new opportunities. He’s making sure that his big bet on esports—devoting his life to what he calls a “risky” profession—will work out, no matter what happens. But some players, Ichetovkin says, don’t put in that effort. “They go all in and it doesn’t work out, and they don’t know what they want to do after,” he said. “It would be interesting to see where a lot of the pro players would be at now.”

Ichetovkin may have already ended up like one of those former pros, destined to be an anecdotal warning to future generations, if he let his circumstances keep him down. But now, he’s back in the LCS after an improbable journey to get there.

The return

Renegades looked unstoppable for most of the Challenger Series. The team blistered the league, jumping to an undefeated 6-0 record through three weeks, establishing themselves as one of the favorites along with Team Coast.

For most of the season, they used Ainslie “Maplestreet” Wyllie at marksman, with the imported Afghan player Tohki sidelined due to a visa issue. When Tohki finally entered the lineup, the team slumped. They lost the first game of two against Vortex in the final week of the season, a missed opportunity to clinch the top seed. That set up a tie breaker against their rival, Team Coast. Renegades lost.

“Training with Jebus was good experience for him and for us, but at the same time it made a lot of issues especially when it was for a couple of weeks,” Ichetovkin said. “A lot of our confidence was broke because we lost against Coast with him.”

Eventually they decided to bring Wyllie back into the fold, but their troubles continued. They weren’t performing well in practice. The usually playful and cheery team seemed close to breaking.

“I’m not sure what was happening at that the time,” Ichetovkin said. “It looked pretty rough. The team was really really upset about losing.”

Some teams might crumble in such a situation—a run of bad form at the worst possible time, with the playoffs on the horizon. Some teams never recover from a slump, forever losing the fire that fuelled their original success. But Renegades pulled together and worked through their issues, just in time for playoffs. Ichetovkin doesn’t point to any specific turning point, but was encouraged by the team’s mental fortitude in putting the slump behind them.

Renegades looked unstoppable for most of the Challenger Series.

“I was really proud of team,” Ichetovkin says. “It was a great feeling. Most of the time, it is usually shows teams the best not when they are winning, but when they are losing. So I was really proud of the team.”

The team earned their LCS berth by winning two close bouts in the Challenger Series playoffs. They beat Imagine Gaming 2-1 in the semifinals before taking revenge on Team Coast in a 3-2 nailbiter with a guaranteed LCS berth on the line. Team Coast eventually qualified for the LCS by beating Enemy in a convincing 3-0 promotion series sweep, meaning a budding rivalry may continue.

Many players would be elated to earn a spot in the LCS. But in some ways for Ichetovkin, it was more a relief. It was vindication. After years of effort, he’s still got it. But more importantly, he’s got security for his job, which means security for his family.

But don’t let that obligation to family fool you—Ichetovkin hasn’t lost his competitive drive. He wants a playoff spot, a chance to win the title or at least earn circuit points towards potentially qualifying for Worlds. That’s a result that eluded the Summer split’s rookie teams, like Enemy, but Gravity Gaming managed to pull it off in the Spring.

“If you don’t set a high goal you will never achieve it,” Ichetovkin explains. “If you won’t achieve it, it will be upset. Okay. But if you don’t set that goal… it’s just too sad to live like that, for me.”

No regrets

A little over three years ago, Ichetovkin’s future presented his wife with a gift, a beautiful ring, days before she planned to visit him in his hometown for a couple weeks. The two lived in different cities, meaning they could only meet for fleeting trysts that never lasted long enough.

When she arrived and embraced Ichetovkin, she was wearing it. He put it on her ring finger. She was floored.

Ichetovkin exemplifies what it means to be an esports veteran and a professional, even at his young age.

“I think she is still surprised that happened, the way it happened,” Ichetovkin said, adding with a laugh. “Though, I’m pretty crazy!” The two had only been dating about three months when they got engaged. It was a whirlwind romance. That may seem out of character for the level-headed Ichetovkin. But in the game, he’s not afraid to take risks if the payout is worth it. And the same goes for his personal life.

Three years later, they’re enjoying the sunny California weather, visiting Hollywood, family and, at least in his case, eating a lot of steaks (one of the most exciting part of life in the U.S., he says). The Ichetovkins live in a two bedroom apartment just a short 20-minute drive from the Santa Monica studio where Riot hosts the LCS. Win or lose, he’ll return to his loving wife and two-year-old child after every match instead of a 1,500 mile flight and eight hours of travel.

After a long and difficult journey, Ichetovkin is content. He’s found a way to balance his family life and his esports life. And while it’s been difficult at times, he says he doesn’t “regret anything.”

“I think regretting is bad,” he says. “You just experience. No matter what you do its experience, no matter if it’s bad or good.”

That’s a philosophy that’s guided Ichetovkin through one of the most winding paths taken by an esports player yet. Most players, even legendary ones, never return when they topple from their pedestal. Some try desperately to claw their way back up, but never reach the same heights.

Yoon “MakNooN” Ha-woon revolutionized the game with aggressive top lane play, but as the Korean scene passed him by, he became increasingly desperate to regain past glory. He came to America seeking redemption, but found only failure.

Other legends return to add new chapters to their careers. This year, Hai Lam became one of those players when he stepped down and retired with hopes of Cloud9 taking the next step to become world title contenders. Instead, Lam had to return to the lineup in a new position to save Cloud9’s spot in the league before taking them on one of the most improbable runs in esports history to arrive at Worlds.

“I really like Hai,” Ichetovkin said. “He’s a really great player. He’s making great history for himself.”

Whether Ichetovkin can return to the heights he experienced at the peak of Moscow Five’s reign remains to be seen, but he’s finally firmly on the climb back up, ready to write new history of his own. And with that kind of perseverance, with a supportive family and solid team behind him, what’s going to stop him? Nothing has so far.

Photos via ESL & Riot Games | Remix by Jacob Wolf

Alex Ich is in, Xpecial is out. Check out our Quick Cast news update on League’s roster roller coaster.

Published: Sep 25, 2015 08:00 am