Pinning a weaker peace to a stronger one greatly reduces the mobility of both and could soon lead to winning some material. They are not always game-ending, though: there are multiple ways to get out of pins, and sometimes you can even turn the tables on your opponent.

What is a pin?

Pins are one of the basic tactical motifs in chess. By attacking a piece that has a more valuable counterpart behind it, it becomes “pinned” and can’t move without a loss of material. Pins are similar to skewers, but in that scenario, the more valuable piece is the one that’s directly threatened. Only bishops, rooks, and queens can pin pieces.

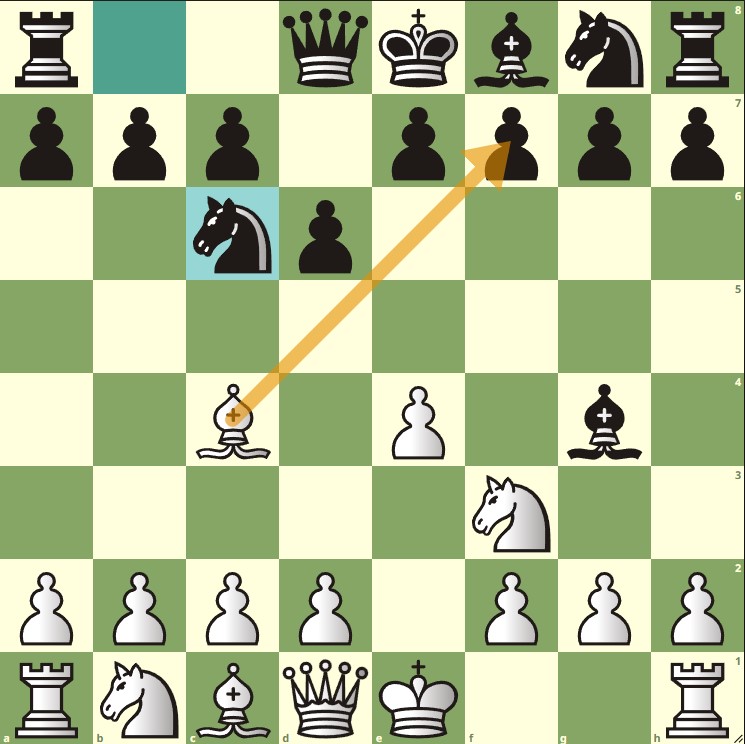

Here is an example of one of the most common pins in the opening:

Quickly developed knights can easily be harassed by bishops due to the value of the king and the queen on the end of the diagonal. The knight on c6 can’t move (since it would be illegal to put your king in check) while his f6 counterpart is greatly inconvenienced. Hopping away would cost the queen.

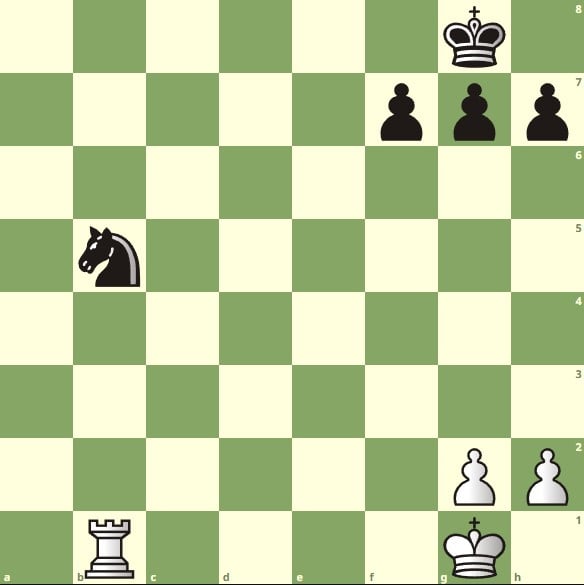

Sometimes you can also pin a piece to a square. Consider the following example:

The poor knight cannot save itself because it would open up the b8 square for the rook, leading to checkmate. It will be captured on the following move.

The best way to make use of a pinned piece is to attack it, preferably with pawns. Since it is struggling to move, it is a juicy target to attack and take out. Because of that, you should try to get out of the pin as soon as possible if your piece has been immobilized.

How to get out of a pin in chess?

There are three ways to deal with a pin (also known as “unpinning”). First, you could move the valuable piece out of the way, freeing up the pinned piece. This generally requires the pinned piece to be protected by something else. You can also remove the pinning piece, either by capturing it outright or by forcing it to move away. You also have the option to block the pin by placing another piece in the line of fire, disconnecting the pinned piece from the valuable target behind it.

Sometimes, pins don’t work out as planned. If the pinning piece is not protected properly, you might jump out of the way with tempo and turn the tables on your opponent. Here is another classic example:

Though it seems like the f3 knight cannot move, a fancy sacrifice on f7 quickly rips black’s plans apart: after Bxf7+ and Kxf7, Ng5 comes with check, exposing the g4 bishop to the vengeful queen on d1, with a capture to follow. Turning around a pin in this fashion is one of the most satisfying things in chess.

Published: Mar 27, 2022 09:55 am