Former world chess champion Vladimir Kramnik may have immediately disavowed the results of his unique little “Clash of Claims” match with José Eduardo “Jospem” Martínez Alcántara after he lost today, but even if you accept all his protestations, his original claims about dodgy play have clearly taken a beating.

Blunders galore

Vladimir Kramnik reminds me of a Garfield comic strip.

I couldn’t quite track it down for you, but it’s Jon, the owner, telling the orange furball that everyone handles aging differently. Then, he asks that maybe Garfield could do so with dignity, as we see the punchline: the cat standing in a diaper and with a pacifier in his mouth, looking rather morose about an upcoming birthday.

It must be tough to be a former world chess champion, now lurching firmly into boomer territory, having to stomach repeated defeats to young whippersnappers in fast-paced online play—players whose abilities he clearly doesn’t rate too highly. Can you really blame the man for looking for external reasons to explain away his defeats? After all, he was once the best player in the world, and the single-minded dedication needed to get that far self-selects a certain sort of people.

In his case, it’s a sort that’s more than willing to overestimate their understanding of technology and statistics and one absolutely unwilling to do any self-reflection. Kramnik has been banging the drums about cheating in online chess for a long while now—a concern shared by many at the highest levels of play, though little foul play has been proven—but the nature and the presentation of his arguments have been much more damaging to his cause than he understands.

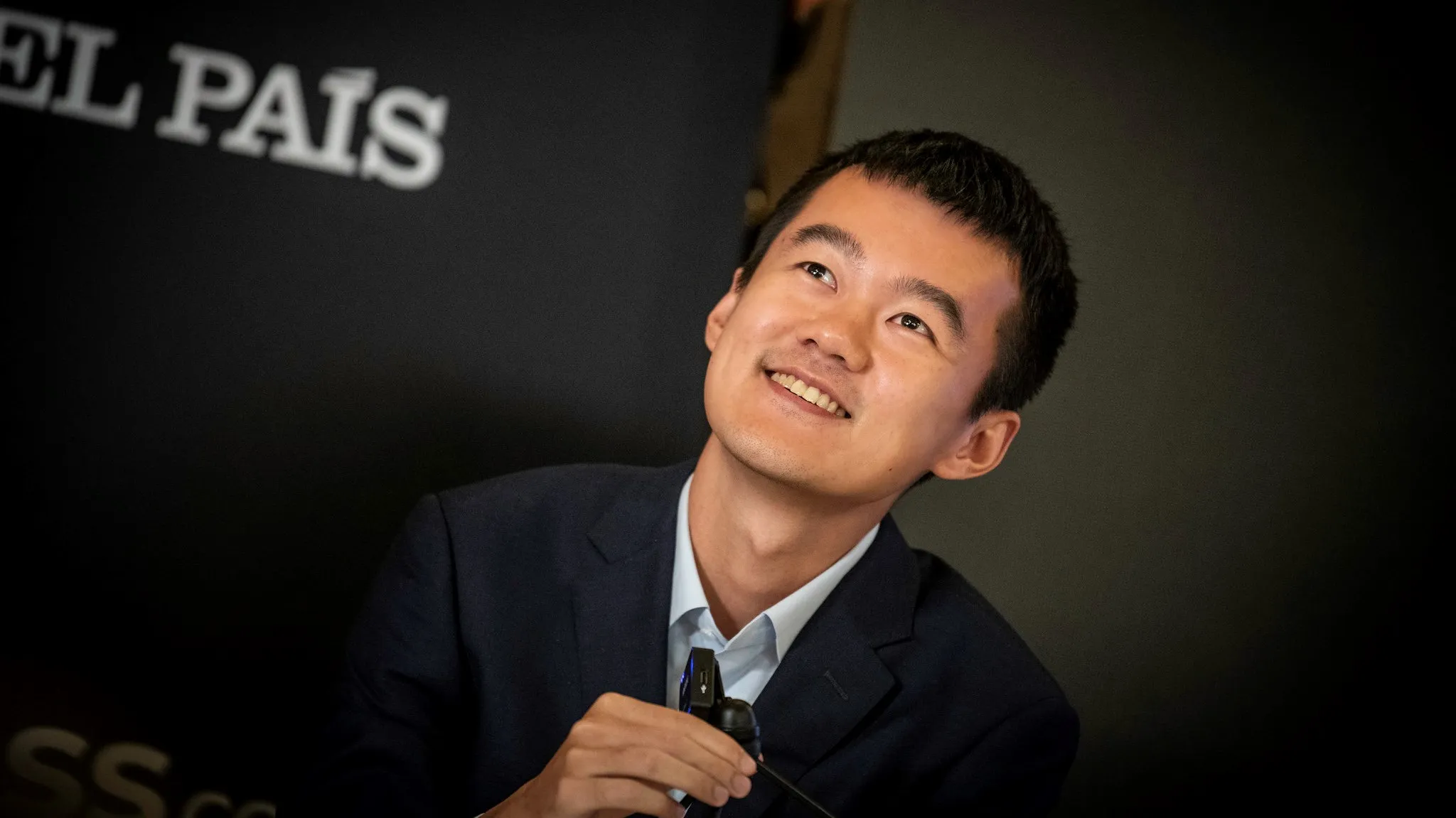

When a former world chess champion speaks out, the chess world listens; seriously at first, then with horror and amusement. Kramnik’s specifics about cheaters have always been woefully lacking, and the man never stopped moving the goalposts. Over and over again, he promised to release specific numbers, mathematical analyses, and smoking guns, but he never did so. And yet, the insinuations never stop. Sometimes it’s Nakamura, sometimes it’s a young up-and-coming talent like Jospem—who, lest we forget, is still a top 200 player in the world over the board—but always, it’s someone who beats him.

To prove his point without offering up real proof, Kramnik chiefly looks at the chess.com accuracy number and the corresponding Elo approximation—a marketing metric cooked up by the whizkid engineers of the site—without factoring in the nuances that come with the differing complexities of the various positions or the clock situation during the game.

Spoiler alert: If my opponent blunders a piece early on, even I, as a patzer, can maintain a super high accuracy and a GM-level average centipawn loss in a game—because it can be easy to do so! Conversely, if both players are low on time in an extremely complicated position, even someone like Carlsen will drop down in this metric. Context is king, but Kramnik keeps focusing on a pawn.

Poorly formulated arguments about cheating in chess are especially sad to see coming from Kramnik, who was himself a victim of such a kerfuffle back in 2006 during a world championship match. If anyone should know how problematic it is to chase ghosts in such a malicious manner, it should be the victim of the infamous “Toiletgate” affair. Then again, this is the same man who once called flagging “moral degradation,” showing a complete lack of understanding of the way online chess is played.

I don’t know what this ill-conceived Clash of Claims match was supposed to prove originally, as the agreed-upon format differed from Titled Tuesdays in multiple important ways, but it was devastating to Kramnik’s case—whatever it might ultimately be.

Kramnik’s loss is everyone’s gain

The topline number is clear as day: 15.5-11.5 in Jospem’s favor, a whopping +6 in the online section. Feel free to discount the final game if you’d like to—the main metric stays the same. But even more importantly, Kramnik’s conduct in a controlled competitive environment was nothing short of disgraceful.

Just like with his arguments, he moved the goalposts over and over again, not abiding by either the letter or the spirit of the contract, repeatedly demanding changes to the format of the match and generating an impromptu break waving around a cell phone and the calculator app as he tried to manually tally up lag totals. It was embarrassing to watch, and full credit to Jospem for keeping his cool and continuing to rack up points along the way.

Yes, there have been confirmed issues with the setup, and I wouldn’t be surprised if there were legitimate server issues involved with the final game. But even if you want to cast doubt on the specific outcome or even contend that Kramnik was somehow worse affected by the issues than his opponent (who, lest we forget, also had to contend with his constant tantrums and non-stop moving of goalposts), the point of this flawed experiment was nevertheless proven.

After all, the question was: Can a player with worse over-the-board showings put up a superior showing when playing online against a strong opponent, and are there online-specific skills at play? Clearly, if you needed any proof, the answer is yes. Not only did Jospem outperform his OTB results by a significant margin, but, more importantly, Kramnik was playing much, much worse after picking up the mouse.

The former world champion played significantly slower and struggled much more to maintain a good level of play in time trouble situations, blundering many times along the way. He may take a page from the sore loser playbook and say the match didn’t count, but the footage of his poor play remains.

Whether it’s board vision, age, “boomer” things—it doesn’t matter: There was a clear difference in Kramnik’s own play between how he performed over a physical board and how he played online. So why couldn’t a shift in skill to the opposite direction be equally as valid, especially as evidenced here?

Some differences between the two modes of play are easy to spot even on an amateur level: You can make premoves online, and you don’t have to manually hit a clock. Also, you can’t fumble your pieces the same way as you could when playing on a physical board, there is no need to make a mad scramble for an extra queen when you promote a pawn, and you physically can’t make an illegal move online—all that before considering that you might spot things differently on a 2D representation than when the third dimension is involved. Surely, everyone can see this.

Everyone but Kramnik.

Instead, he will keep staring at the match footage in his hotel room tonight, trying to find his lost youth and dignity. Unfortunately, not even the greatest grandmaster can find those on the sixty-four squares.

Published: Jun 9, 2024 08:06 pm